Here is my translation of Premchand's short story 'Shatranj ke Khiladi'. This is sixth of the most popular short stories of Premchand translated by me and posted on this blog. Hope lovers of Premchand would enjoy reading it. I have used the Hindi version of the story for my translation.

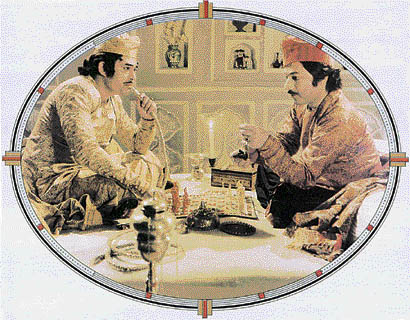

A scene from Satyajit Ray's film

The Chess Players

(शतरंज के खिलाड़ी)

It was in the times of

Wajid Ali Shah. Lucknow was drowned in sensuality. The big and small, the rich

and the poor – all were sunk in it. Some were engrossed in dance and music;

some just revelled in the drowsiness induced by opium. Love of pleasure

dominated every aspect of life. In administration, in literature, in social

life, in arts and crafts, in business and industry, in cuisine and custom –

sensuality ruled everywhere. The state officials were absorbed in fun and

pleasure, poets in descriptions of love and separation, artisans in zari

and chikan work, businessmen in dealings in surma, perfumes and

cosmetics. All were drowned in sensual pleasures. No one knew what was

happening around the world. Quail fights were on. Rings were being readied for

partridge fights. Somewhere the game of chausar was being played, with

its attendant shouts on the winning throw. Elsewhere a pitched chessboard

battle was on. From the king to the

pauper – all were engrossed in these pleasures. So much so, that if beggars received

money in alms, they preferred to spend it on opium or its extract rather than

bread. ‘Playing games like chess or cards or ganjifa sharpens the mind,

improves mental faculties and helps in solving complex problems.’ Such

arguments were being forcefully advanced. (People subscribing to this thesis

can be found even today.) So if Mirza Sajjad Ali and Mir Roshan Ali spent most

of their time sharpening their wits, how could any thoughtful person take

exception. Both of them were hereditary Jagirdars,

free from the worries of a livelihood; they enjoyed their good food

without having to work at all. What else could they do?

Every morning, after

breakfast, both the friends would spread the chessboard, set up the pieces

and engage themselves in the tactics of

chessboard warfare. They would forget whether it was noon, afternoon or

evening. Repeated messages from inside that food was ready were ignored, and

the cook was forced to serve food right there in the room, as the two friends

continued their play. There were no elders in Mirza Sajjad Ali’s family; as a

result the game was played in his dewan khana. However, members of

Mirza’s family were far from pleased. Not to speak of the family, even the

neighbours and servants made uncharitable comments: ‘This is an inauspicious

game and can ruin families. God forbid that anyone should get addicted, for it

makes a person unfit to do anything.

It’s a serious disease.’ Mirza’s begum was so hostile to the game that

she would seek out occasions to berate her husband. But she rarely got this

opportunity. The game would begin while she was still asleep, and Mirza would

come inside only when she had gone to sleep. However, she would expend her ire

upon the servants. ‘Are they asking for paan? Tell them

to come and take it themselves. Have they no time for food? Go

and throw it to them. Let them eat or cast it to the dogs.’ But

face to face she was helpless. She wasn’t resentful against her husband so much

as against his friend, Mir sahib. She had named him Mir, the spoilsport.

It is possible Mirza, to save his own skin, also threw all the blame on Mir

sahib.

One day the begum had a

severe headache. She said to her maid, ‘Go and call Mirza sahib. They should go and bring medicine from a

hakim. Run, be quick.’. Mirza sent the maid back saying he

would follow. The begum was hot-tempered. She lost her patience. How could her

husband play chess while she had a headache?

Her face became red with anger. She said to the maid, ‘Go and tell them

to come immediately, or I shall go to the hakim by myself.’ Mirza was in the

midst of a very absorbing game. Mir sahib would be checkmated just in two

moves. He spoke in irritation, ‘Is she on her last breath? Why can’t she

wait?’

Mir sahib interjected,

‘Why don’t you go? Women are delicate things.’

Mirza retorted, ‘Oh

yes, you want me to go because you’re facing defeat in the next two moves.’

Mir said, ‘My dear,

don’t be under any illusion. I have thought of a counter move that’ll turn the

tables on you. Go and attend to her. Why are you hurting her?’

‘I won’t go until I have

checkmated you.’

‘I won’t make any moves. Go and attend to

her.’

‘My dear, I’ll have to go to a hakim. There’s

no headache. This is just pretence to harass me.’

‘Whatever it is, you’ll

have to go.’

‘All right. Let me make

one more move.’

‘Not at all. I won’t touch my pieces until you

have gone and talked to her.’

When Mirza sahib went

in, the begum changed her tactics and said, groaning with pain, ‘You love this

wretched game so much that you don’t care even if I am dying. What kind of a

man are you?’

Mirza replied, ‘What

could I do? Mir sahib wouldn’t let me go.’

‘Does he think all are

as idle as he. He too has a family. Or has he finished them off ?’

‘He’s such an addict.

Whenever he comes I am forced to play.’

‘Why don’t you drive

him away?’

‘He is my equal in age,

and two fingers higher in rank. I have to oblige him.’

‘Ok, then I shall drive

him away. What if he is offended? Does he feed us? Oh Haria, go and pick up the

chessboard. And tell Mir sahib that Mirza sahib won’t play anymore. Tell him to

go home.’

‘No, no! Don’t

do anything of the kind. Would you have me humiliated? Oh Haria, stop. Don’t go.’

‘Why don’t you let her

go? Anyone who stops her will drink my blood.

All right, you stopped her. Let me see how you stop me.’

Saying this begum

sahiba advanced angrily towards the dewvan khana. Mirza’s face turned pale. He began

to plead with her. ‘For God’s sake. I bind you in the name of Hazrat Hussain. You would

see me dead if you went there.’ But the begum was in no mood to listen. She

walked up to the dewan khana, but she stopped. She wouldn’t go in, in the

presence of an outsider. She looked in but there was no one there. Mir sahib

had displaced a few pieces on the board and had gone out for a stroll to show

his innocence. The begum went inside and overturned the chessboard, threw some

chessmen under the dewan and a few others out through the door. Then she shut

the door and bolted it from inside. Mir sahib saw the chessmen being thrown out

and heard the sound of bangles, and the door being bolted. Realizing that the

begum was inflamed he slnnk away.

Mirza sahib said to his

begum, ‘You’ve been terrible.’

The begum retorted, ‘If

Mir sahib comes here, I shall drive him away from the doorsteps. Had he devoted

himself to God like this he would have become a saint. You keep playing chess

and I remain enslaved to the domestic chores. Are you going to the hakim, or

are you still unwilling?’

Mirza came out, but

instead of going to the hakim he went straight to Mir sahib’s and narrated the

whole story.

Mir sahib replied,

‘When I saw the chessmen being thrown out, I understood everything and ran. She

seems so hot-tempered! But you have pampered her so much. This is not good. Why

should she bother what you do outside? It is her duty to manage the household.

Why should she worry about what you do?’

‘Never mind,’ said

Mirza, ‘Where shall we play now?’

“Why worry? This is a

big house. We can play anywhere here.’

‘But how shall I make

the begum accept this? When I sat at home she kept on creating trouble. Now if

I sit here she won’t let me breathe.’

“Let her shout. She’ll

get used to it in a few days. But from now onwards be a little tough with her.’

2

For some unknown reason

Mir sahib’s begum preferred to have her husband away from home. That’s why she

never objected to Mir sahib’s love of chess, so much so that if Mir sahib

delayed going out she would remind him. Because of this Mir sahib was under the

illusion that his wife was very courteous and sober. But when the chessboard

was spread in the devan khana and Mir sahib stopped going out, the begum

became edgy. Her freedom was curtailed. She hardly had any chance to have a

glimpse of the outside.

And there was murmuring

and whispering among the servants. Up till now they had sat idle, warding off

flies. They were never bothered by guests. But now they had to take orders the

whole day. Now to fetch paans,

now sweets. And the hookah kept smouldering like a lover’s heart. They would go

and complain to begum sahiba. ‘Mirza sahib’s chess has become a nuisance.

Running about to execute orders, our feet are blistered. What sort of a game is

this that goes on from morning till evening! It should be enough to play a game

for an hour or two. But we can’t complain. We’re his slaves and have to obey

the orders. But this game is evil. The person playing it never prospers. A

misfortune is bound to fall upon such a house. So much so that we have seen

whole neighbourhoods being ruined one after the other. Everyone in the

neighbourhood is talking about it. We’re his faithful servants and don’t like

to hear him maligned.’ On this begum sahiba would say, ‘I also don’t like this.

But he doesn’t listen to anyone. What can I do?’

In the neighborhood

there were a few people of the old school. They had begun to foresee many

unhappy consequences. ‘Nothing good will come of

it. When our aristocracy is behaving in this manner, God alone can save the

country. This kingdom will be ruined because of this game. It’s an evil sign.’

And indeed there was

great disorder in the kingdom. People were being robbed in broad daylight.

There was no one who could listen to their complaints. All the wealth from the

countryside was being sucked into Lucknow and blown on prostitutes, buffoons

and in sensual pleasures. The blanket of debt to the English Company was

becoming wetter and heavier every day. Because of the absence of good

administration taxes were not being collected fully. The Resident was

constantly threatening but people were so drenched

in voluptuous pleasures, that not a flea tickled their ears.

Nevertheless, months

passed and the game of chess went on in Mir sahib’s dewan khana. Newest

strategies were being charted, newest castling moves devised. There would be

arguments and accusations, but soon the two friends would be reconciled.

Sometimes the game would be terminated midway, and the estranged Mirza sahib

would walkout and go home, and Mir sahib would go inside. But the night’s sleep

would dissolve yesterday’s resentment and the two friends would be back in

the dewan khana.

One day the two friends

were submerged in the quicksand of chess when an officer of the king’s army

came riding on a horse asking for Mir sahib. Mir sahib was stunned. What was

this? Why these summons? This was no good. He shut the doors and said to the servant,

‘Tell him I’m not at home.’

“Where’s he, if not at

home?’ asked the rider.

‘I don’t know. What’s

the matter?’ asked the servant.

‘I can’t tell you. He

has been summoned. May be, he has to provide some soldiers for the king’s army.

Jagirdari is no fun. If he has

to go to the battlefield, he’ll know what it is.’

‘All right, your

message will be delivered.’

‘It’s not that. I shall

come again. I have been ordered to bring him along personally.’

The rider went away.

Mir sahib was terrified. He said to Mirza sahib, ‘Now, tell me what to do?’

‘It’s big trouble. Even

I may be summoned.’

‘He said he would come

again.’

‘This is a calamity.

What else! If we have to go to the battlefield we would meet an untimely death.’

‘There’s only one way out. They should not

find us at home. We can spread our board somewhere on a lonely spot on the bank

of Gomti. No one will know. And the fellow will return empty-handed.’

‘Wonderful! Nothing can

be better than this.’

And here at home Mir’s

begum sad to the rider, ‘You’ve given him a good rebuke.’

The rider said, ‘I know

how to make such fools dance to the click of my fingers. All their sense and courage has been eaten away

by chess. Now they won’t stay at home even by mistake.’

3

From the next day both

the friends would leave their homes before dawn. With a small mat under their

arms, holding a box-full of paans

the two friends would make their way across the river Gomti to an old deserted

mosque that had been built perhaps by Asaf-ud-Daula. On their way they would

buy tobacco, a chillum and wine; and they would enter the mosque, spread their

mats, light their hookah and start playing. Then they would forget the world.

No other words except ‘check’ and ‘mate’ would come out of their mouths. No

yogi would be so focused in his meditations as these two. When in the afternoon

they felt hungry they would go to an eatery and eat something; smoke their

hookah for a while and then restart their play. Sometimes they would forget

even to eat.

On the other side, the

political situation in the kingdom was deteriorating every day. The Company’s

forces were advancing upon Lucknow. The city was in a great turmoil. People

were fleeing to the villages with their families. But our two players were

unconcerned. They came out of their houses and sneaked through narrow lanes,

hiding themselves from the eyes of the king’s men. They wanted to enjoy the

benefits from their Jagirs

yielding thousands of rupees annually by doing nothing in return.

One day both the

friends were playing chess sitting in the decrepit mosque. Mirza’s position was

somewhat weak. Mir sahib was threatening him with ‘check’ after ‘check’. In the

meantime they saw the soldiers of the Company passing by. It was the gora army moving towards Lucknow to

capture the city.

Mir sahib said, ‘The

English army is advancing. God be kind.’

Mirza said, ‘Let it

come. Check. Save your king.’

‘Let’s watch. Let’s

stand in a corner.’

‘Do that later. What’s

the hurry? Check.’

‘They have the

artillery too. There must be some five thousand men. Their faces red like

monkeys! One is afraid to look at them.’

‘Janaab, don’t make excuses. Don’t use these ruses. Check.’

‘You’re a strange man.

Here the city is in danger, and you’re only thinking of “check and mate”. Have

you thought how we shall go home if the city is besieged?’

‘We shall see when it

is time to go. Here is check. And mate.’

The army marched away.

It was ten o’clock. A new game was set up.

Mirza said, ‘Where

shall we eat?’

‘It’s a roza day

today. Are you feeling very hungry?’

‘Oh, no. God knows

what’s going on in the city!’

‘Everything must be as usual. People must have

eaten and would be sleeping peacefully. Nawab sahib must be having fun in his

harem.’

Both of them set up

another game. It was three in the afternoon. This time Mirza’s position was

shaky. The four o’clock bell was ringing as they heard the sound of the army’s

return. Nawab Wajid Ali had been captured and the army was escorting him to an

unknown destination. There was no commotion in the city, and no fighting. No

bloodshed. Nowhere the king of a free country would have been vanquished so

quietly, without any bloodshed. It wasn’t the kind of non-violence that would

please the gods. It was a form of cowardice on which even great cowards would

have shed tears. The king of a vast country like Awadh was being driven away as

a prisoner, and the city of Lucknow was sleeping peacefully. This was the

nether of political downfall.

Mirza said, ‘The

tyrants have captured Nawab sahib.’

‘Never mind. Save your

king.’

‘Wait a minute, janaab.

I can’t concentrate at the moment. Poor Nawab sahib must be shedding tears of

blood.’

‘He should. He won’t

enjoy these luxuries there. Check.’

‘All days are not the

same. What a painful situation!’

‘That’s true. Here,

check again. Now it’s mate. There’s no escape for you.’

‘By God, you’re so

cruel. You are unmoved even after such a great calamity. Oh, poor Wajid Ali

Shah!’

‘First you save your

own king. Mourn for Wajid Ali Shah later. Here’s check and mate. Give me your

hand.’

The army marched away

with the king as their prisoner. Mirza laid another game as soon as they were

gone. Defeat is always painful. Mir said, ‘Come on, let us sing an elegy to

mourn Nawab sahib’s fall.’ But Mirza’s loyalty to the king had disappeared with

his defeat. He was bent upon taking revenge.

4

It was evening. In the

ruins the bats had begun to flutter and scream. The swallows had returned to

their nests. But the two players were still playing, as if two bloodthirsty warriors

were engaged in a mortal combat. Mirza had lost three successive games and the

fourth one too didn’t seem to be going his way. He was playing with the

determination and caution, but each time some move somehow went wrong and

weakened his position. His desire for

revenge was sharpened with each defeat. On the other hand, Mir sahib was

bursting into ghazals, and teasing Mirza sahib, as if he had unearthed a secret

treasure. Mirza sahib was irritated but he would utter words of praise for Mir

sahib to overcome his embarrassment. But as his position progressively weakened

he was losing his patience, so much so that he was losing control over himself.

‘Now don’t change your move again and again. What’s this? You make a move and

then change it. Make your move only once. Don’t touch a piece unless you are

moving it. You’re taking too much time. This is against the rules. If someone

takes more than five minutes to make a move he should be treated as the loser.

Now you changed your move again. Please put the piece back.’

Mir sahib’s vazir was

about to be taken. He said, ‘I haven’t moved yet.’

‘You’ve made your move.

Please put the piece back where it was.’

‘Why should I put it

back? I had never let it go from my hand.’

‘If you don’t let go

your piece till eternity, does it mean you haven’t moved it? Now when your vazir

is being taken you have started cheating.’

‘It is you who is

cheating. Winning or losing is by luck. No one wins by cheating.’

‘Then, you have been

checkmated in this game.’

“Why have I been checkmated?’

‘Ok, then replace the

piece in the same square.’

‘Why? I won’t do it.’

‘Why not? You’ll have

to.’

Tempers were rising.

Both were unwilling to yield. Then the argument took a different turn. Mirza

said, ‘You would have known the rules if someone had played chess in your

family. Your ancestors were grass-cutters. How could you learn to play chess?

Nobility is something different. One does not become a nobleman just by

receiving a jagir.’

‘What? It is your

father who must have been a grass-cutter. In our family we have been playing

chess for generations.’

‘Oh leave it. You have

spent your life working as a cook at Gazi-ud-din’s. To become a nobleman is no joke.’

‘Why are you blackening

the faces of your ancestors? They must have been cooks. Our family has

always dined with kings.’

‘You grass-cutter,

don’t make tall claims.’

‘Hold your tongue. I’m

not used to listening to this kind of language. If someone stares at me I pluck

out his eyes. I dare you.’

‘You want to test my

courage? All right, let us test each other’s to the end.’

‘I’m not afraid of

you.’

Both the friends drew

their swords from their hips. It was the age of chivalry. Everyone was equipped

with a sword or a dagger. Both friends were pleasure-loving but no cowards.

They had become devoid of political will. Why should they die for kings or

kingdoms? But they were not deficient in personal courage. The fight began. There was thrusting and

parrying; the swords flashed and clashed. And both, fatally wounded, fell down and

died writhing in pain. They who could not spare a

single drop of tear for their king died defending their vazirs on the

chessboard.

It was getting dark.

The pieces still lay on the chessboard. It was as if both the kings sitting on

their thrones were shedding tears at the death of these warriors.

Silence reigned all

around. The broken arches, the ruined walls and dust-laden pillars of the

mosque were watching these corpses and cursing their fate.

---

(Hindi,

Madhuri, October 1924)

thank u very much... It was a pleasure reading it....

ReplyDeleteand a quite apt translation...

thank you for the translation--I will share the link with my friends.

ReplyDeletethank u so much.... pleasure reading this story...

ReplyDeleteIf it wasn't for your translation I would not have been able to read this story. Many, many thanks.

ReplyDeleteI remember reading this story as a kid. Thank you so much for posting this translation!

ReplyDeletetnkx now i can do my hindi project

ReplyDeleteits too long it must be summarized

ReplyDeleteIt is a translation not a summary

Deletevery apt translation... was happy reading it...

ReplyDeleteThank you so much! This has been really helpful :)

ReplyDelete